William Howard Taft

POTUUS: The Oval Office and Unitarian Universalism

- William Howard Taft Bio

- Address at the Laying of the Cornerstone of the Universalist Church in Irvington, Portland, Oregon

- The Religious Convictions of an American Citizen

William Howard Taft: 27th president of the United States, 10th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and a Unitarian.

Born 1857 in Cincinnati, Ohio, William Howard Taft came from a well-known Republican family. His family was affiliated with the First Unitarian Church in Cincinnati. Taft’s father Alphonso had rejected the Baptist faith to become Unitarian, and young Will attended Sunday School there. He followed in his father’s footsteps in other ways as well.

Taft went to Yale University and studied law. He was an excellent lawyer, and his career was furthered by his family’s political connections. His father, Alphonso, had served as Secretary of War and Attorney General for President Ulysses Grant. And so, Alphonso’s son rose in politics through his own competence and because, as he once wrote he always had his “plate the right side up when offices were falling.”

President Benjamin Harrison appointed Taft solicitor general and later made him an appeals court judge. Taft enjoyed being a judge, and he hoped to be on the Supreme Court. But in 1900, President William McKinley asked Taft to help set up a new civilian government for the Philippines after the Spanish-American War. Taft served as the first non-military governor. Sympathetic toward the Filipinos, he improved the economy, built roads and schools, and gave the people at least some participation in government.

In 1904, Taft accepted appointment as Secretary of War for President Theodore Roosevelt. Taft traveled the globe and advised Roosevelt on both military policy and foreign policy. They were good friends, and Roosevelt became convinced that Taft shared his philosophy of a “progressive” government.

Roosevelt had promised not to seek a third term in 1908, so he endorsed Taft as his successor. However, during this campaign on the Republican ticket, his liberal faith surfaced after he received countless letters saying that a Unitarian atheist should not be allowed to occupy the White House. The Hartford Herald newspaper accused him of looking upon Jesus of Nazareth not as savior but as a “common bastard and low, cunning impostor.” Nevertheless, nationally Taft won an overwhelming victory.

But it soon became clear that Taft’s presidency would not resemble Roosevelt’s. Taft recognized that his techniques would differ from those of his predecessor. He used laws rather than executive power or force of personality to forward his agenda. Taft once commented that Roosevelt “ought more often to have admitted the legal way of reaching the same ends.”

Within those constraints, Taft did support the Progressive Movement. He formed the Interstate Commerce Commission; and also expanded U.S. foreign trade through investment in what became known as “dollar diplomacy” increasing U.S. influence in Latin America and East Asia.

The Taft era Congress submitted two Constitutional amendments to the states that were ratified in 1913: the sixteenth amendment created a federal income tax; the seventeenth amendment authorized the direct election of senators. Taft appointed FIVE judges to the Supreme Court during his term in office. In 1911 that Supreme Court ordered the dissolution of the Standard Oil Company and the American Tobacco Company for being in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act, and that’s just two of 80 anti-trust lawsuits Taft had filed.

In the 1912 election, the Republicans renominated Taft, but he lost the Oval Office to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Taft, free of the Presidency, became president of the General Conference of Unitarian and other Christian Churches from 1915-1925, at which time the General Conference was absorbed by the American Unitarian Association. He served as Professor of Law at Yale until President Warren Harding made him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1921. To Taft, the appointment was his greatest honor; he wrote: “I don’t remember that I ever was President.” He served on the Supreme Court until his poor health compelled him to retire. He died on March 8, 1930 at the age of 72 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

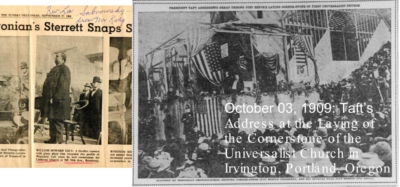

President Taft’s Address at the Laying of the Cornerstone of the Universalist Church in Irvington, Portland, Oregon, on October 03, 1909

I don’t know that anybody questions the propriety of my attendance on this occasion, or that it is necessary for me to enter into an explanation. I conceive it to be the duty of the President of the United States to welcome and encourage and support every instrument by which the standard of morals and religion in the community may be elevated and maintained. It was my pleasure and my opportunity to take part in the dedication of an orthodox Congregational Church in Washington in the spring; my pleasure to take part in ceremonies in a Jewish tabernacle in Pittsburg; to officiate as the layer of the cornerstone of a Roman Catholic university at Helena, and now to take what part I may in the ceremonies of laying the cornerstone of a Universalist Church in this beautiful suburb of Portland. And I do it because I believe that the cornerstone of modern civilization must continue to be religion and morality.

We have in our Constitution separated the civil from the religious. It was at one time my good fortune to visit Rome in order by negotiation to effect a settlement of a number of questions which had arisen between the Roman Catholic Church and the civil government in the Philippines. The government of the Philippines under Spain had illustrated that system known in the Spanish Government as the union of Church and State. Their interests were so inextricably united that it seemed almost impossible to separate them but with the consent and acquiescence of all denominations in this country, I was authorized to go to Rome to meet the head of the great Roman Catholic Church, in order to see if those matters might not be settled amicably. I am glad to say that the result of the visit was a satisfactory settlement, equitable and just to both sides.

But I started to mention it in order to relate that I ventured to say to the Pope that the division between Church and State in this country and their separation was not in the slightest degree to be taken as an indication that there was anything in our government or in our people which was opposed to the Church and its highest development, and I ventured to point out that in the United States the Roman Catholic Church had flourished and grown as it had not grown in many European countries, and that it had received at the hands of the government as liberal and as just and as equal treatment as every other church; no better and no worse; but that that was not to be taken as an indication that every officer of the government properly charged with his responsibility would not use all the official influence that he had to encourage the establishment of churches, their maintenance and the broadening of their influence in order that morality and religion might prevail throughout the country.

This is a Universalist Church, known as a liberal church. I think it must have been a Universalist who said that the Universalists believed that they would be saved because God was good; that the Unitarians believed they would be saved because Unitarians were good. But whatever the creed, we have reached a time in this country when the churches are growing together; when they are losing the bitterness of sectarian dispute; when they appreciate that it is necessary, in order that their influence be felt, that they stand shoulder to shoulder in the contest for righteousness. They believe in the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man; and the real broad Christian statesman is glad to accept from every quarter the assistance which will elevate the people and lead them on in that progress that we all believe the American people are making. If they are not attaining higher moral standards, then all this material progress, all this advance in luxury and comfort is worth nothing.

I am an optimist. I believe we are better to-day than we were fifty years ago, man by man. I believe we are more altruistic. I believe that each man is more interested in his fellow than he was fifty or one hundred years ago. I know you can point to instances of self-depravity, of selfishness and greed, but I believe those instances are made more prominent because we condemn them more, and because by being made prominent the happening of them is made less likely.

I am glad to be here. I hope this church will thrive. I hope it will maintain its high principles of making a good man and a good citizen and mixing them together. I welcome the opportunity to be able as President of the United States to say there is no church in this country, however humble, which preaching true religion, which preaching true morality, will not have my support and my earnest effort to make it more successful when opportunity offers.

Description: Taft’s own Presidential flag given to a Universalist Church during cornerstone laying ceremony in 1909, with outstanding provenance.

…

EDITOR’S NOTES: In early October 1909, President Taft was completing a Western Tour of the United States, and drawing attention to its varied religious communities. Taft had previously attended worship services, lectures, and other sponsored events at Mormon, Jewish, Catholic, Unitarian, and Universalist places of worship. On October 3, 1909 in Portland, Oregon, President Taft attended a Sunday service at a Unitarian Church, met with Catholic school children, and then participated in a cornerstone laying ceremony at the First Universalist Church of Good Tidings located at 24th Street and NE Broadway. Approximately 15,000-20,000 Portlandians attended the last ceremony. The October 4, 1909 issue of the New York Times reported that Taft was very engaged in the cornerstone laying ceremony: “The President not only talked, he handled the silver trowel and worked hard to see that the stone was properly adjusted”. Taft then placed a number of items, including possibly the flag on Lot 227, into a metal box that was then placed into the cornerstone.

Unfortunately, the church did not thrive as Taft originally intended. After a decade, a Lutheran church took over the space, eventually selling to the Metropolitan Community Church in the late 1970s. The Metropolitan congregation merged and moved away to North Portland, so that in 2021 SteepleJack Brewing, serving burgers and craft beers, opened its first location in the 111 year old building.

THE RELIGIOUS CONVICTIONS OF AN AMERICAN CITIZEN

An address delivered as President of the General Conference of Unitarian and other Liberal Christian Churches.

Taft, William Howard. The Religious Convictions of an American Citizen. United States: American Unitarian Association, 1904.

It has been my lot to be the chief executive for four years of an Oriental people more than seven millions in number-Christians, Mohammedans, and Pagans. I have been chief executive of the American people for a similar period and have had other experiences in the government of these two very different peoples. The longer and more intimate my knowledge of their political and social lives, the more deeply impressed I have become with the critical importance of the part that the Church and religion must play in making popular government what it ought to be, and in vindicating it as the best kind of a government that an intelligent people can establish.

The necessity for the infusion of the religious spirit into the prevailing morality for the purpose of giving it life and persistent influence is a fact that every one who studies the life of a people from the standpoint of a responsible administrator of government must recognize. There are doubtless many

individuals who live a moral and upright life, who are not conscious of religious faith or feeling or fervor; but however this may be in exceptional cases, it is the influence of religion and its vivifying quality that keeps the ideals of people high, that consoles them in their suffering and sorrow, and brings their practices more nearly into conformity with their ideals. The study of man’s relation to his Creator and his responsibility for his life to God energizes his moral inclinations, strengthens his self-sacrifice and restraint, prompts his sense of paternal obligation to his fellow-man, and makes him the good citizen without whom popular government

would be a failure.

If it be said that this view of the need of religion and its value is not as high as it should be because it looks chiefly to progress in human welfare and happiness in this world rather than in the next, I can only say that the character and needs of this world we know, while we can but surmise the features of the next. Milton’s words, which he put into the mouth of his real hero, Satan, “The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven. of hell, a hell of heaven,” we can verify by this world’s experiences. We may rest reasonably satisfied that the religious spirit and conduct which help to create heavenly human happiness in this life will not be out of keeping with life hereafter.

The tendency of the Christian world toward greater liberality in creed is interesting to trace. In the sixteenth century few believed in religious tolerance, one faith and creed was right, all others were wrong, and it was the duty of the orthodox to force their creed on all for the glory of God and for the saving of the unbelievers. It was better to use compulsion with him, even to his death, to induce conversion, because if obdurate in his unbelief he was bound for eternal torment anyhow.

Erasmus, in the sixteenth century, was a note-worthy exception. He believed in religious toleration and resented the restrictions upon him, a priest of the Church, which a different rule entailed. The Papists and the Puritans conceded the logic of each other by the same intolerance; and the Puritans of New England, who sought her rocky shores in search of freedom to worship God in their way, denied it to others and banished Roger Williams to his Providence colony, which became a refuge for all schismatics.

Various influences prevailing when our National Government was formed secured complete religious freedom and tolerance. The logic of the doctrine of individual responsibility to God taught by the Puritans ultimately led in New England to independence of religious thought and toleration of differences in creed. The Friends, under Penn, had always upheld it. The Catholics of Maryland, with a charter from an Anglican throne, favored it. Jefferson was a Unitarian, and fought the fight of religious freedom in Virginia. Some of the States retained tests of eligibility to the electorate and to office, based on religious creed, but these soon disappeared.

The first Amendment to the Federal Constitution declaring for freedom of religion and against any establishment of a state church, although at first only a restraint upon the Federal Government, soon represented the attitude of all the States on the same subject.

Under complete freedom of religion, liberal thought is bound to assert itself. The intensity of persecution does not then destroy a sense of proportion as to the essentials of a faith and its incidents. Channing’s sermons and the schism in the very home of orthodoxy followed. While the law as to freedom

of religion was sweeping, the attitude of the orthodox churches and of society, which they dominated, was still intolerant and severely condemnatory.

Gradually, however, the views of many in the evangelical churches have grown more liberal, and in the generation through which I have lived, I can see a marked change of attitude toward Unitarianism and liberal religion.

My father and mother were Unitarians; my mother’s mother was a Unitarian who followed Channing. Liberal religion was therefore bred in my bones. After a life of nearly threescore and of a not inconsiderable contact with many religions, I do not find my views changed as to the profound importance both of maintaining the Christian religion as an indispensable element in the progress of civilization to better and higher ideals and of the persistent upholding of liberality in Christian religious thought as a means of stimulating and elevating the lives of those whose faith in a strictly orthodox creed has failed and who, but for a broader religious outlook, might drift into indifference and lose the inspiration of religion that all men need.

Now, what are Unitarians? Are they Christians? Of course, that is a matter of definition. If a man can be a Christian only when he believes in the literal truth of the creed as it is recited in the orthodox evangelical churches, then we Unitarians are not Christians. A Unitarian believes that Jesus Christ founded a new religion and a new religious philosophy on the love of God for man, and of men for one another, and for God, and taught it by his life and practice, with such Heaven-given sincerity, sweetness, simplicity, and all-compelling force that it lived after him in the souls of men, and became the basis for a civilization struggling toward the highest ideals. Unitarians, however, do not find the evidence of the truth of many traditions which have attached themselves to the life and history of Jesus to be strong enough to overcome the presumption against supernatural intervention in the order of nature. They feel the life of Jesus as a man to be more helpful to them, as a religious inspiration, than if he is to be regarded as God in human form. They find in the higher criticism of the Gospels reason enough to explain those passages in which the supernatural is set forth as part of Jesus’ life and doctrine, as additions to a much simpler story upon which the synoptic gospels were founded. They learn that the composer of each gospel had a bent and a motive which colored his rendition of an earlier story, and that the prompting to do so was found in early controversies in the Church between Jews and Gentiles. They realize that the grandness of style and the doctrinal character of the Fourth Gospel were well suited and were necessary to the strengthening of the Christian Church, as it then was, among the people of the civilized world. But they deny that they lose the essence of Christianity when they give up miracles, the Virgin birth, and the deity of Jesus. The Unitarians have always emphasized the life of Jesus in his teaching of love as the foundation of all things spiritual, and the motive and end of the Kingdom of God. In that sense, and that we believe to be the true sense, Unitarians are Christians.

The views which Unitarians have avowedly adopted as their faith have forced themselves, in one form or another, into the minds of many laymen and some clergymen of orthodox churches. They have softened the rigidity of a narrow insistence on literal acceptance of every dogma. They have liberalized the attitude of many of the evangelical churches. Many orthodox clergymen have done away largely with the doctrinal sermon and with attacks upon differing creeds. Instead, they exalt, as they should, the profoundly helpful example of Jesus’ life and his pregnant parables and lessons of love and true happiness in seeking the Kingdom of God. They dwell upon the purpose of all his actions, embodied in the sentence: “And Jesus went about doing good.” Not only that, but they are making their churches centers of doing good. They are showing the essence of Christianity by their works of helpfulness. Many modern churches have become institutional in the organization of branches for philanthropic, charitable and educational progress among those for whom they feel responsible. While I do not say that this change indicates a general surrender by church authorities of the tenets of the orthodox Christian creed, it indicates a change of emphasis that enables many laymen to remain within the church whose minds tend toward more liberal Christianity. This change has, I believe, strengthened the churches in their useful and elevating influence upon society, and it has brought all churches closer together in a common advance. There is more team work among them.

This tendency has modified the attitude of orthodox churches toward Unitarians in a large degree. It has promoted a spirit of tolerance and friendly co-operation. It was not always so. Jefferson, though a sincere student of the teachings of Jesus and a Unitarian, was denounced as an atheist. We know the contumely, insult, and mob violence to which Priestley was subjected in England. Franklin, the Adamses, and Fillmore were really Unitarians, but they were looked at askance. Lincoln, one of the most deeply religious men, was clearly Unitarian in his faith. In spite of all these illustrious examples, religious prejudices have been played upon in politics to defeat Unitarians and upholders of liberal Christianity and in very recent years; but even in the time my life compasses, I can see a great change for the better.

When the intolerance was great, when the real feeling of the orthodox clergy and laity was, in its spirit, out of harmony with the constitutional declaration in favor of freedom of religion, it was necessary for Unitarians to be militant, and to deal blow for blow in controversy, and to give reasons for the faith

that was in them. But now that the struggle for liberal Christianity has so largely prevailed, now that it is showing itself in the orthodox churches themselves, and in their laity, we can be content to maintain our Unitarian congregations and fold, still comparatively small in number, knowing that, consciously or unconsciously, our attitude and the scientific spirit of modern days in Biblical criticism have revealed, in its proper lines, the real essence of Christianity, and have blurred doctrinal and denominational distinctions in a union of effort to follow the teachings and religion of the life of Jesus Christ. The office performed by Unitarianism in this respect has been one of the highest importance in retaining for many men and women of strong intellect, independence, and courage of thought, the consolations and strengthening inspiration of religious faith and their responsibility to God, without the necessity of professing beliefs which to them are unproven and unprovable.

A people without religion are lacking in the greatest aid to the progress of society through the moral elevation of individuals and the community. A church and a faith which reconciles religion and freedom of thought and retains the essence of a Christianity and which has done so much to redeem the world and advance it in ‘real happiness toward the Kingdom of God, has a right to claim a reason for being. It is not for us to attack the faith of other Christians. It is not for us to rouse in them the doubts that have troubled us in accepting their creed. It is not for us to deny the good their faith does them or

the comfort their religion gives them. It is for us to encourage all churches where they are working, as they all are working, for the good of man, and where we can unite with them or express our general sympathy with them to do so.

The Young Men’s Christian Association I consider one of the greatest practical agencies for saving young men from dissipation and degradation and for stimulating them to useful and moral lives. In those to whom it offers its encouraging facilities it makes no distinction of creed or religion. It is non-denominational except that by one of the rules of its original organization, its directors must be members of an orthodox Protestant evangelical church. This has been made the basis for severe criticism of its narrowness. I cannot share this view. The rule of eligibility to the directorate was adopted in an earlier period and perhaps would not be insisted on were it being organized today. The whole administration, however, is now so catholic and liberal and so world-wide in its usefulness that this feature does not trouble me. When I think that, in China, mandarins, who are Confucianists or nothing, contribute generously to Young Men’s Christian Association establishments because of the good it does in the large cities of the far Orient, I don’t think it is for a Unitarian to withhold his aid and encouragement merely because he is not eligible to its directing leadership. My life has fallen in places in which the importance of the spread of civilization by foreign Christian missions has deeply impressed itself on me.

My advocacy of all Christian foreign missions is not based, I hope, on a narrow view of other than the Christian religions. The earlier spirit of our Christian missions was narrow and tended to defeat itself in its bitter contempt for, and opposition to, other religions. The wider, more catholic, and, I think I may say, the more Christian spirit which actuates them now recognizes the good there is in the great religions like the Mohammedan and Buddhist faiths in keeping before the minds of their followers the capital importance of their relation to God. The great advance which the Christian religion promotes with them is in enlarging their religious conception to appreciate the ever loving fatherhood and close companionship of God, the importance in His eye of the individual, and the mitigation of the sternness and aloofness of the God of their religions. The Christian missions have performed a great office with pagan peoples. By their good works in establishing hospitals and furnishing medical aid, in founding schools, and in the sacrifices that the missionaries and their families make to help the people with whom they live, they offer incontestable evidence of the spirit of the Christian religion, whose ministers they are.

They have not converted to Christianity from other religions as many as one might wish, from a statistician’s point of view, considering the expenditure of life, money and effort in the work; but they have founded centers of influence and power among millions of pagan peoples from which each year and each decade are spreading the idea that government is for the welfare of the people and that Christianity and Democracy are closely associated.

The political changes taking place in China, India and Africa are much affected by the Christian missions, whose heads are consulted by the leaders and rulers of the peoples who recognize the position the missionaries have attained in the respect and confidence of those among whom they have gone about doing good.

It was a great pleasure to enjoy membership in All Souls’ Church in Washington, D.C. during my incumbency as chief magistrate and to contribute some effort toward the construction of a great National Unitarian Church edifice at the Country’s Capital. Many of the statesmen of the country in the past have been members of that church.

I have come to the close of my remarks. The creeds and dogmas that attached themselves to the religion of Jesus, needed perhaps in securing its spread among the nations and its triumphal march to a better civilization, have encountered the searching freedom of scientific intellectual inquiry, and have shaken in the minds of many, not the essential principles of the Christian faith as we Unitarians believe them to be, but the incidental tenets of a rigid theology. In order that the craving for religion and a study of man’s relation to God should still act as an inspiration to human self-elevation and moral progress, Unitarianism offers a broad Christian religious faith that can be reconciled with scientific freedom of thought and inquiry into the truth, and rescues from religious atrophy and indifference an element of society that must be influential. Indirectly, too, it has liberalized the requirements of other churches so that they retain in their laity and under elevating religious influence an important part of the community that otherwise might drift away. These are the good things that Unitarianism has done and is continuing to do.